Guest post by Margaret Skea

For some writers research is a chore, but that wasn’t the case with me when I decided to write a biographical novel based on the life of Katharina von Bora, Martin Luther’s wife. There are relatively few books about her, and one author opens his (slim) volume with this sentence: “It is impossible to write a biography of Katherine Luther, neé von Bora.” (Martin Treu*)

For some writers research is a chore, but that wasn’t the case with me when I decided to write a biographical novel based on the life of Katharina von Bora, Martin Luther’s wife. There are relatively few books about her, and one author opens his (slim) volume with this sentence: “It is impossible to write a biography of Katherine Luther, neé von Bora.” (Martin Treu*)

So there I was, wanting to write a novel about an historical person about whom almost nothing is known. A gift to the historical novelist? Well, perhaps.

Treu goes on to write that this dearth of sources has “tempted authors and authoresses to fill in the gaps with their own imagination. The result of this is frequently enough a picture that says more about the writer and their time than about the person and journey through life of Katherine von Bora.”

Did I want to write a book that said more about me than it did about Katharina? No, I didn’t. A biographer must strive to avoid bias, but a writer of biographical fiction can choose whether to strive for objectivity, focus on fiction, or – as in my case – seek to steer a course between the two.

Katharina von Bora, the renegade nun who became Martin Luther’s wife, is a fascinating and enigmatic character. There is debate over her parentage, her birthplace and the circumstances surrounding her admission to two different convents. Her subsequent escape, as one of a group of twelve, is the first recorded ‘mass’ breakout following Luther’s revolutionary teachings. There is more information from the time of her arrival in Wittenberg onward, though even that is incomplete, and sometimes contradictory.

There is little documentary evidence of her personality: only a handful of letters written by Katharina remain. It is possible, however, to catch glimpses of her from surviving letters that are written to her, particularly by Luther, as well as through the reactions of others and via her reported actions.

I relished the challenge of seeking to find a ‘voice’ for Katharina. However, as someone who is passionate about historical authenticity, I was concerned not to step outside the bounds of what was plausible and could be defended by reference to the historical record. As a result, my writing was a juggling act between what I wanted Katharina to say and be and what might have been possible for her at the time.

As a child Katharina was placed in two convents, one Benedictine, and one Cistercian. Studying their rules and practices was a starting point. So was researching the impoverished German knightly class – Katharina’s family background. It helped me imagine why certain decisions were made about her future.

I have to admit to succumbing to one legend, which from a novelist’s point of view was irresistible – that her father’s remarriage contributed to her being sent to the first convent at around the age of five – though I tried to soften the ‘evil stepmother’ image.

It was more difficult when it came to the adult Katharina. Records of the Nimbschen convent where she lived from c 1509 – 1523 contain no censure of her, so clearly she did not cause her superiors concern. And yet she was part of a mass breakout at Easter 1523. How she came to that point can only be speculation, but I made sure it was grounded in facts.

For example, I chose not to use the popular legend that the nuns escaped hidden in herring barrels. While the idea may be attractive from a dramatic point of view, it is highly impractical. Being bounced along some 30 miles from Grimma to Torgau in the back of a wagon would be uncomfortable enough, but folded into a barrel which normally contained fish? I don’t think so.

In addition to reading about life in 16th-century Saxony, I went there myself to experience the physical surroundings through Katharina’s eyes. I walked where she had walked, stood where she had stood, and handled things she might have handled. I was fortunate to be given a grant by Creative Scotland which resulted in a two-week solo trip that involved driving 1,000 miles in a circular tour of Saxony.

Much of what existed in Saxony 500 years ago has disappeared, but the Black Cloister in Wittenberg remains. Now called the Lutherhaus, it was her marital home, and it is preserved well-enough for me to imagine what it would have been like to live there in her time.

I also visited Luther’s birth house, stayed in the building he died in, spent one night in a room overlooking the famous ‘Theses’ door of Wittenberg’s Castle Church, and one in a monastery cell. Although more comfortable than it would have been in 1517, its size and location adjacent to an internal cloister gave me a sense of enclosure.

Aside from that, the magnificent Yadegar Asisi 360° Panorama of Wittenberg of the early 16th century allowed me to see every aspect of life through changing images and sounds over the equivalent of a 24-hour period. The details were exquisite, the whole Panorama seething with life. The longer I stayed, the more I saw, and many of the details that contribute to the atmosphere in the book come from that Panorama.

One of the greatest benefits of research travel are the unsought and unexpected discoveries. Would I do it all again? In a heartbeat … now where can I set my next book?

* Treu, Martin. Katharina von Bora Luther’s Wife, Reformation Biographies, English Edition, Drei Kastanien Verlag (2016), page 5

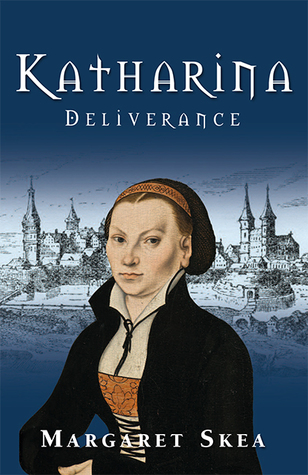

Katharina: Deliverance was published in both print and e-book in October 2017, exactly 500 years after Martin Luther displayed his 95 theses on the Wittenberg church door, an event which is credited with sparking the Reformation.

Originally from Ulster, and now living in the Scottish Borders,

Originally from Ulster, and now living in the Scottish Borders,

Margaret Skea is an award-winning historical fiction and short story writer. Her Scottish novels, also set in the 16th century, are Turn of the Tide and A House Divided. You can visit her website at www.margaretskea.com

Thank you, Patrycja, for having me on your blog.

LikeLike

You’re welcome. Thank you for educating me and other readers about this fascinating woman.

LikeLike